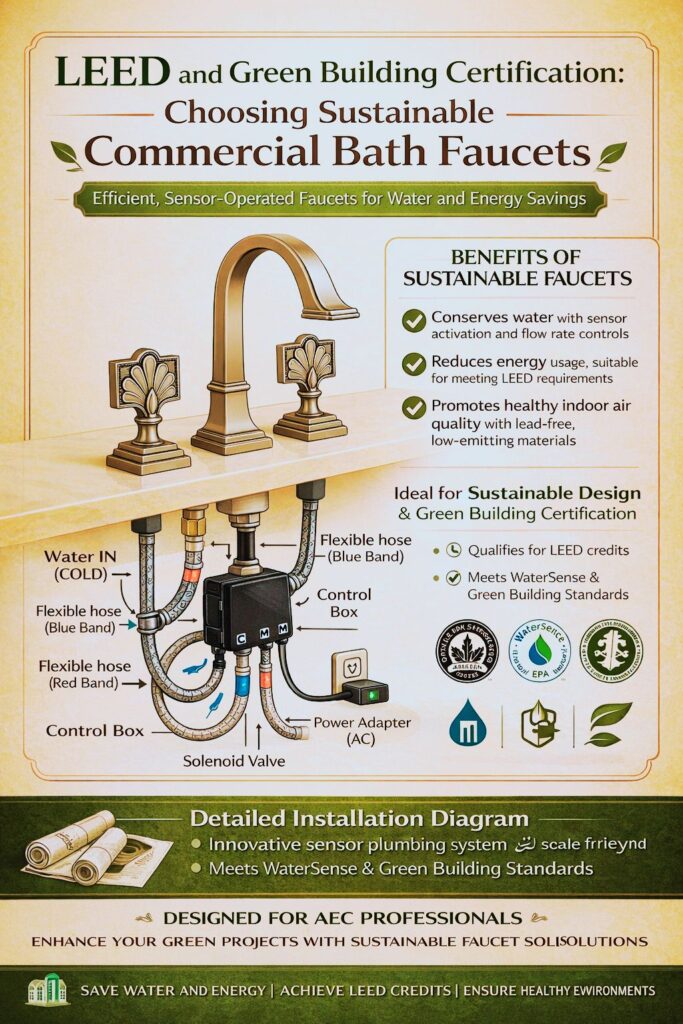

Commercial restrooms don’t always get the spotlight in sustainability discussions, but in most building types they account for a predictable, repeatable source of potable water use—often across dozens (or hundreds) of lavatories. That makes commercial bath faucets a practical lever for green building performance.

For AEC teams pursuing LEED or other certification programs, sustainable faucet selection is not about picking the “greenest” marketing claim. It’s about choosing fixtures that can be modeled, documented, and operated reliably—while supporting water efficiency, reducing hot-water demand, and meeting health-related compliance expectations.

This guide focuses on how specifiers can select commercial bath faucets that align with LEED indoor water goals and broader green building criteria, without turning the fixture schedule into a sales pitch.

🔗 LEED / USGBC indoor water reduction guidance

Where faucets show up in LEED and green building documentation

In LEED, faucets are most directly tied to Indoor Water Use Reduction. USGBC guidance notes that compliance and credit achievement are typically demonstrated through fixture performance data and calculations, and that reductions can be assessed as a combined whole across project buildings in certain approaches.

🔗 USGBC Indoor Water Use Reduction – Documentation Guidance

What makes faucets important in certification workflows is that they influence multiple measurable outcomes:

- Potable water use (flow rate and duration)

- Hot-water draw (which affects energy and carbon outcomes indirectly)

- Submittal quality (third-party labels and consistent documentation reduce review friction)

- Health and compliance (lead and drinking-water component standards may be requested by owners and required by code in certain contexts)

In short: faucets affect both performance and paperwork.

🔗 LEED Indoor Water Use Reduction – USGBC

Indoor water reduction: what AEC teams actually need from faucet submittals

LEED documentation relies on consistent, verifiable performance information. If faucet data is unclear or contradictory across cut sheets and schedules, it becomes a time drain for the project team.

For most projects, specifiers should capture the following for each lavatory faucet type:

- Flow rate in gpm at a defined pressure (commonly expressed at 60 psi)

- Operating mode (manual, metering, sensor)

- Flow-control/aerator part number matching the claimed gpm

- Evidence of third-party certification where applicable

- Consistency across documents (cut sheets, spec, product page, submittal)

This matters because indoor water calculations are only as accurate as the fixture performance assumptions and the documentation supporting them.

🔗 Indoor Water Use Reduction Requirements – USGBC

WaterSense as a defensible efficiency baseline for lavatory faucets

When teams want a clear, recognizable starting point for water-efficient lavatory faucets, EPA WaterSense is one of the most widely referenced programs.

EPA notes that WaterSense labeled bathroom sink faucets and accessories use a maximum of 1.5 gpm and can reduce sink water flow by 30% or more from the standard 2.2 gpm flow rate without sacrificing performance.

🔗 EPA WaterSense bathroom faucet efficiency baseline

The WaterSense technical guidance further clarifies that the 1.5 gpm requirement is tested at 60 psi.

https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2023-08/ws-homes-TRM-3-BathroomSinkFaucetsTechSheet.pdf

Why this matters for LEED-focused specifications

Even when WaterSense is not an explicit project requirement, it often helps AEC teams because it provides:

- A consistent efficiency cap (1.5 gpm at 60 psi)

- Performance criteria designed to maintain usability

- A recognizable label that simplifies procurement and review

- Easier support for water-efficiency narratives and owner goals

Practical caution

Lower flow does not automatically equal better outcomes. If flow is too low for user expectations, occupants may spend more time at the sink (or re-trigger sensors repeatedly), potentially eroding predicted savings. Sustainable selection means balancing efficiency with real-world behavior.

Public lavatories: code limits and procurement constraints are part of “sustainable”

Many sustainability discussions overlook the fact that public-use restrooms may be governed by more stringent flow limits than private-use bathrooms—especially in public buildings, education, healthcare, and certain state or municipal contexts.

DOE’s Federal Energy Management Program notes that public lavatory faucets are often required to meet 0.5 gpm maximum flow (and that metering faucets must discharge no more than 0.25 gallons per cycle).

https://www.energy.gov/femp/best-management-practice-7-faucets-and-showerheads

EPA’s commercial guidance also highlights that EPAct addressed metering faucets and set the 0.25 gallons per cycle maximum for these public restroom applications.

https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2023-06/ws-commercial-watersense-at-work_Section_3.3_Faucets.pdf

Why this affects LEED outcomes

This is where many teams run into a real-world tension:

- LEED modeling and water reduction strategies may encourage low-flow selection

- But public lavatory code or procurement standards may already push flows toward strict minimums

- At extreme low flows, user experience and hygiene behavior become part of the performance equation

The sustainable choice often becomes the one that meets code, supports LEED calculations, and still provides a usable hand-washing experience.

Sustainability is not only water: material safety and drinking-water contact standards

In green building work, sustainability is increasingly tied to occupant health and the safety of materials that contact water.

The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission advises looking for faucets that comply with NSF/ANSI 61 and NSF/ANSI 372, which establish criteria for drinking-water system product safety and lead-related requirements.

https://www.cpsc.gov/Safety-Education/Safety-Education-Centers/Lead-in-Water-Faucets

NSF also provides consumer guidance explaining that faucets sold in the U.S. are required to meet lead leaching requirements of NSF/ANSI/CAN 61, and that certification is often noted on packaging and may appear on the product.

https://www.nsf.org/consumer-resources/articles/faucets-plumbing-products

Why AEC teams should care

Even when LEED points focuses on water use, owners and authorities may require evidence of compliance with NSF drinking-water standards for fixtures and components. Including these requirements in specifications can prevent last-minute substitutions, RFIs, or compliance gaps during procurement.

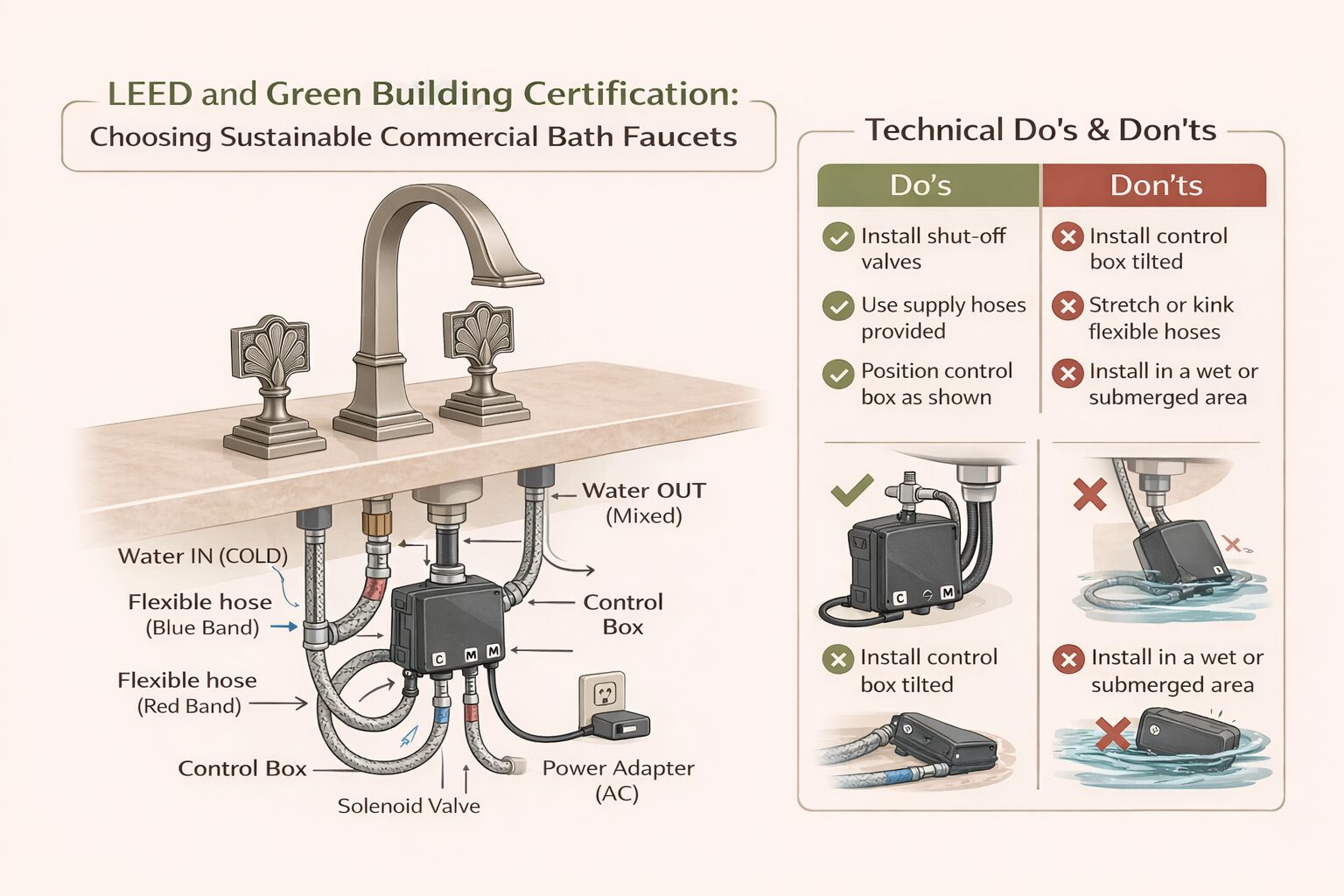

Sensor vs. metering vs. manual: operational performance drives actual sustainability

A green building doesn’t perform sustainably if fixtures don’t behave predictably or are difficult to maintain. Faucet type affects actual water use because it changes how long water runs and how often it activates.

Key factors for AEC evaluation include:

- Sensor accuracy and false activations

- Shutoff delay / run-on time

- Metering cycle length (too long wastes water; too short frustrates users)

- Pressure variability performance (especially in low-pressure buildings or older infrastructure)

- Power strategy (hardwired vs. battery) and replacement access

- Maintenance realities (cartridge availability, solenoids, vandal resistance)

If a faucet meets a low-flow requirement but creates service issues, users and facilities teams may override settings, swap components, or replace fixtures—often reducing the lifecycle sustainability benefit.

Commercial-specific context on how the public lavatory requirements and operational behavior intersect with performance outcomes for faucets is provided in the EPA’s WaterSense at Work section.

A spec-ready checklist: selecting sustainable commercial bath faucets for LEED-aligned projects

You can apply this checklist to link faucet specification to LEED documentation requirements, code restrictions, and performance realities.

A) Water performance (primary certification relevance)

- Confirm the stated gpm at a defined pressure (commonly 60 psi)

- Ensure the installed aerator/flow-control matches the claimed gpm

- Use WaterSense as a benchmark where appropriate (max 1.5 gpm at 60 psi)

https://www.epa.gov/watersense/bathroom-faucets - For public lavatories, verify code/procurement limits (often 0.5 gpm max; metering 0.25 gpc)

https://www.energy.gov/femp/best-management-practice-7-faucets-and-showerheads

B) Documentation quality (prevents LEED and submittal delays)

- Use manufacturer cutsheets with clear model numbers and configurations

- Avoid flow-rate ambiguity across spec sections and product pages

- Reference third-party listing tools when needed (WaterSense product database)

https://lookforwatersense.epa.gov/

C) Health and materials compliance

- Require documentation for NSF/ANSI 61 and NSF/ANSI 372 where applicable

https://www.cpsc.gov/Safety-Education/Safety-Education-Centers/Lead-in-Water-Faucets

https://www.nsf.org/consumer-resources/articles/faucets-plumbing-products

D) Operational durability

- Pick the configurations suited to the conditions (public toilets with heavy usage, vandal-resistant)

- Ensure that maintenance access is provided, if required, and that

- Ensure that sensor/metering settings for minimizing waste are valid and do not impair usability

Common mistakes that cause LEED documentation problems (and performance shortfalls)

Even experienced teams run into predictable faucet pitfalls:

- Specifying a faucet series but not the flow-control configuration

Many models offer multiple flow options. Submittals must identify the installed aerator/flow device. - Assuming all lavatories are treated the same

Public lavatories often have different code-driven flow requirements than private-use sinks.

https://www.energy.gov/femp/best-management-practice-7-faucets-and-showerheads - Over-optimizing for low flow without commissioning the behavior

Sensor delay, activation thresholds, and metering cycle length can create unintended water use.

https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2023-06/ws-commercial-watersense-at-work_Section_3.3_Faucets.pdf - Ignoring drinking-water component compliance

Health-related standards (NSF/ANSI 61, NSF/ANSI 372) are frequently requested by owners and can become a late-stage compliance issue if not addressed early.

https://www.cpsc.gov/Safety-Education/Safety-Education-Centers/Lead-in-Water-Faucets

https://www.nsf.org/consumer-resources/articles/faucets-plumbing-products

Conclusion: the “sustainable” faucet is the one that models, documents, and performs

For LEED and green building certification teams, sustainable commercial bath faucets selectes using three lenses:

- Performance: verified flow rates, appropriate operating mode, and realistic user outcomes

- Documentation: clear submittals and third-party references to support calculators and certification review

- Lifecycle reliability: maintainable components, stable operation, and settings that support actual savings

The best result is not necessarily the lowest gpm—it’s a faucet that helps projects meet certification targets while staying functional for occupants and facility managers for years.

- LEED / USGBC indoor water reduction guidance usgbc.org

- EPA WaterSense bathroom faucet efficiency baseline epa.gov

- WaterSense technical sheet (lavatory faucets, 1.5 gpm at 60 psi) epa.gov (PDF)

- DOE FEMP: public lavatory flow and metering limits energy.gov

- EPA WaterSense at Work (commercial faucets guidance) epa.gov (PDF)

- CPSC: lead in water faucets and NSF/ANSI 61 & 372 guidance cpsc.gov

- NSF consumer guidance: faucets and plumbing products (NSF/ANSI/CAN 61) nsf.org

- WaterSense product database (for verifying labeled products) lookforwatersense.epa.gov

Location: Austin, TX

Profile: Sustainable design consultant specializing in low-flow, touchless water delivery systems. Focused on water conservation strategies and system integration for LEED and Green Globes projects.

No responses yet